”Thou hast made us for thyself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee…

St. Augustine

“Amal is no more,” whispered a friend, in a muted voice, at the other end of the phone. “He left a few minutes ago.”

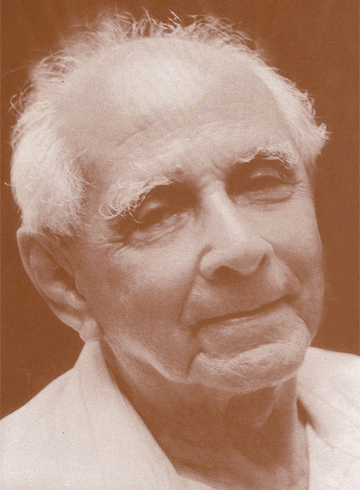

A long silence followed. The words that I had been dreading for decades had been uttered. Ever since I had met Amal, exactly two decades ago, and had made him my best friend, I had wanted him to live forever. I could not imagine a world without him. He had made me who I was. He used to call himself the Pygmalion who had chiselled the Galatea out of me. I was eighteen and he eighty—eight when we met for the first time. But, from the very start, we got along like long lost friends. The friendship seemed rooted in ages. In response to the letter I had written to him after our first meeting, he wrote, “Just as I am present to you the moment you close your eyes, so also you are fixed in my memory in a most vivid way. The accompanying feeling is as if you have emerged into recognition from some depth in me where you were quietly nestling.” These lines filled my heart with warmth adequate for a lifetime.

Being with him made me feel completely secure, understood and loved, as if I were cherished and held in the hollow of his hand—the care, attention and affection showered by him was unsurpassed and unparalleled. I used to often wonder—if Amal had not been there, how could I have ever found such complete understanding and support? How could I learn and grow and live? Such thoughts would result in an overflow of gratitude in my heart towards him. Along with it would also come the fear of losing him.

And now it was happening right in front of me. Amal had gone. How come the world had not collapsed? How come it was still carrying on its petty business of living, as if nothing had happened? How come nothing was changing? How come I was still alive and breathing, the sun still shining, the breeze still blowing, and the flowers still blooming?

Though Amal had been bedridden and indisposed for a while towards the end, his wrinkle-free, lustrous face and his ageless countenance had made us feel that he, like Bhishma, would live forever. Even while his body was being lowered into Mother Earth, I felt that he would sit up, smiling, at any moment and give us a happy surprise. So it took some time for the unbelievable news to sink in. And when it did, memories of a lifetime were relived in an instant. It is strange how the entire past can distil itself into one feeling, one sensation—in this case, that of an irreparable loss, not felt to be of a personal nature alone, but as if the whole world was going to miss something forever—the sweetness and strength of the inmost psyche, which radiated out in every thought, word, and action of Amal’s.

I had first met Amal at the Nursing Home in 1991. A meeting that was supposed to have been scheduled for 15 minutes extended to two long hours. Time had, as if, tiptoed silently past, unnoticed. In the course of the conversation against “the flush of crimson across the sky” outside the window, I had mentioned to him that I do not have a best friend in this world. Immediately, he had offered, “You can make me your best friend.” I did not accept it very enthusiastically because I had thought then that there would be a gap of a few generations between us, and being old, he would not be able to relate to me. But as the friendship progressed, I realised that there was a generation gap, no doubt, but it was the other way round; he was ahead of me in his thinking, more modern in his outlook, and I was the old-fashioned one!

This meeting changed my life. I was a mere child when I first met him. I had many questions about the aim of life, the purpose of living, and the eternal questions like ‘Who am I?’ Not only did he put me on to the path of finding answers to these deep questions of the spirit, but he was also my finishing school in matters of the world, for, to him, they were not mutually exclusive. In fact, one seamlessly complemented the other. He made a lady out of me, as it were, correcting my pronunciation, my ‘Indianisms’ and other incorrect idiomatic expressions in English, and teaching me general etiquette and table manners. On one occasion, while having lunch with him, when I bent slightly over the table to have a bite, he corrected me, “Always sit straight while having food. Remember, you should never go to the food, it is the food that should come to you.” And with that, he downed a perfect spoonful with a perfectly straight back as a demonstration of the lesson.

After I finished my MBA, I opted for a career in Chennai because I sought to combine the best of both worlds this way. Work during the week in Chennai and visit Pondicherry in the weekend. I used to start on Saturday mornings and, after a quick darshan at the Samadhi on reaching Pondicherry, rush to Amal’s house, where he would be waiting for me for lunch. One day, my vehicle broke down on the way. Since mobile phones had not come of age then, there was no way I could inform Amal about the delay. Instead of 12 p.m., I reached Amal’s house at 2 p.m. And what do I see? He was sitting in his wheelchair, near the door of his house, with the front gate open, waiting for me, without having had his lunch. When his friends and neighbours, on seeing him there, had asked him what he was doing, he had told them, “I am waiting for Gitanjali.” He refused to have lunch when they asked him to do so and told them that he would wait till I came. When I reached and saw him there at the door, I was humbled beyond words. I wheeled him inside and served him food. Then I asked him, “Amal, what have I done to deserve so much of your love and care? I am so small and insignificant in every way. Why do you lavish so much of your attention on me?” Without answering me directly, he remarked instead, “On the contrary, I often wonder how you can bring yourself to enjoy so much the prehistoric company of this fossil. The fossil, of course, feels highly flattered on being brought so charmingly up to date.” It was this self-effacing humility that endeared him to one and all.

Though I was a student of physics and mathematics in my undergraduate days, it was Amal who instilled in me the love for literature. And he did it more by example and influence and less by instruction! He used to say that, one should, in order to write great poetry, also read great poetry because then one creates an atmosphere around oneself which is conducive to the flow. He would keep quoting from Sri Aurobindo’s Savitri and the rest of His collected poems, especially His Sonnets, from Shakespeare, Shelley, and, every now and then, from his own collection of poetry, and end his recitations with a question rendered musically, “Who said that?” This quizzing improved my knowledge of literature tremendously because not only would he reveal the name of the poet, but also the deeper meaning and symbolism of the verses, comparing and contrasting them with similar or differing verses by other poets. He would also teach me how to recite Savitri, how to differentiate the pronunciation of the words which began with a ‘v’ and those that began with a ‘w’ by making me repeat ‘very well’ after him. It was also amazing to see him win hands down repeatedly in a game that we used to play, a game in which one opponent says a word and the other recites a poem containing that word in the first line. One day, out of sheer admiration for him, I said, “Amal, I want to become like you,” and he began to recite from his poem, At the foot of Kanchenjunga:

Become like thee and soar above

My mortal woe

And to the heavens passionless

And mute, from dawn to dawn address

Thoughts white like snow.

The lines flowed absolutely flawlessly, and I asked him, surprised, “Amal, how is it that when you speak, you sometimes stammer, but when you recite poetry, you don’t?” He said, “How can I when, instead of blood, it is poetry that flows in my veins.”

I once asked him who he would have liked to have been in his last birth, and promptly came his reply, “Dante,” the famous Italian poet, whose Divine Comedy is considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature.

It was his book, Light and Laughter that drew me to him. The book had such a deep impact on me that I went to SABDA and picked up all 14 copies that they had left and distributed them among my friends. A few years later, when I went to pick up some more copies, I was told that the book was out of print. Then and there, I vowed that of all the things that I would do in this life, one would be to have a publishing company that would keep Amal’s books always in circulation! Though the task was taken on instead by the Clear Ray Trust, that thought of mine perhaps became the seed for founding Helios Books, several years later.

Once, when I reached Amal’s home, I found a few people there engaged in some intense discussions. Since Amal was not a participant, he could welcome me and spend time with me. After some time, when I asked him out of curiosity what those people were discussing, he said that they were exploring the possibilities of nominating him for the Nobel Prize for Literature! “Why are you not participating in the discussion then?” I asked him, surprised. “Who cares for the Nobel Prize,” he said dismissively, “when my poems have been seen and appreciated by Sri Aurobindo Himself!”

Our favourite topic of conversation was always the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. For those of us who have not had the chance of meeting Them physically, it is always a royal treat to hear about Them from the fortunate ones who have. I would ask him about how They looked, how They spoke, how They smiled, how he felt when he was with Them and so on. My biggest regret in life was this: that I had missed meeting Them physically. Amal sensed this unspoken sadness and remarked one day, “One cannot but love Them after having met Them. It is easy. But to have this love for and trust and faith in Them without having met Them is something remarkable.” This thoughtful consolation did bring a smile to my face. When I asked him how he had felt on first meeting the Mother, he said, “She was Beauty incarnate,” and his sigh at that time, like St. Augustine’s, was, “Too late have I loved Thee, O Beauty so ancient and so new, too late have I loved Thee!” And Amal had been only 23 at that time!

Just as Einstein could explain the Theory of Relativity effortlessly to a child, Amal could explain the deepest of metaphysical truths easily because he had assimilated them so integrally, not only in his mind, but in his entire being. Recently, when I asked him to explain Sat, Chit and Ananda, he replied, “Sat is that which never changes; Chit that changes all the time, and Ananda is that which expresses both.” How beautiful and succinct, I thought! Encouraged, I delved further, “What is Reality or Truth?” He replied, “God realising his own dream.” It is this poetic touch and his lucid expression of original research on the most difficult topics that make Amal’s books my favourite read.

“What is my swadharma?” I asked him once. “A combination of Brahmin and Kshatriya,” he replied, “because, like me, you not only seek the Truth, but, if required, can fight for it and lay down your life for it.” Surprised, I asked, “You, a Kshatriya? I thought you were a Brahmin through and through.” He replied, “The moment I was born, the big lamp in our drawing room flared up. My father had to run from my mother’s side to prevent a fire. The English lady doctor who was attending on my mother considered the flaring lamp as an omen and said, ‘The boy will be a great man.’ She perhaps went beyond her brief and should have just said, ‘The boy will be a fiery fellow’ because, from the very start, I displayed a very hot temper. It is quite possible that I might have become a soldier or a man of action had my steps not been dogged, literally, by misfortune that came in the form of infantile paralysis.” The samurai-like spirit with which he used to defend Sri Aurobindo’s works and His philosophical ideas in his letters to people who had misunderstood Him was ample evidence of this aspect of his temperament. Whenever I would display a similar streak, he would fondly and lovingly call me “pocket Amazon”—the miniature version of Penthesilia, the notable queen of the Amazons, the women warriors of classical antiquity.

Amal broke all moral and conventional stereotypes and looked at the real thing instead. For instance, he used to tell me, “What is so spiritual about getting up at 4 am?” What he meant was that just the act of getting up early means nothing, especially if it is accompanied by a sense of pride and a superiority complex. The most important thing was the attitude of surrender, of equality, and of remembering and offering, at every moment in one’s life. He always emphasised being free, even from the so-called ‘virtues’. Born in a vegetarian family, I was averse to the sight and smell of non-vegetarian food. Not only could I not stand its sight, but its smell made me feel nauseated. One day, when I was having lunch with Amal, he asked me to have a piece of chicken. I was surprised at his request. But he explained to me that, in yoga, repulsion or aversion is as bad as slavery or attraction. And one should be free in the mind with regard to everything. Since, by then, I used to follow every advice of Amal blindly, I just closed my eyes and ate a tiny piece of the chicken. The taste was nothing to write home about; it reminded me of soya chunks—fibrous and rubbery. But the after-effect was that I became absolutely free from it; the repulsion had vanished. It helped me a great deal because, when I lived in the hostel during my MBA days, fellow students sitting all around me at the canteen dining table would be having non-vegetarian food and I could bear it. Had I not overcome the aversion, I would have starved. He told me once that this freedom and wideness of mind was perhaps the reason he never had a headache in his entire life.

Similarly, when I wrote to him once that I was unable to attend get-togethers and parties as I could not bring myself to do the ‘small talk’ that is required, he wrote back, “I don’t advise too much seclusion. Books, no doubt, are fine companions, but some touch of common things is healthy and necessary in the conditions under which you live at present. To be cut off from people calls for great inner resources if one is not to become morbid. A bit of frivolity, which is not lost in a swarm of triviality, can be accepted:

A little non-sense now and then

Is relished by the wisest men.”

One day, I wrote to him: “Amal, I always feel a kind of push from within to be better than what I am, to improve, improve and improve. Is it ‘vital’ because it sometime leads to impatience?” He replied, “This push you feel is not ‘vital’ but ‘psychic’. Its giving rise sometimes to impatience does not necessarily imply that it is vital. Face to face with

The heavy and weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world

the aspiring soul is occasionally apt to exclaim: ‘How long, O Lord, how long?’ The suspicion of personal ambition enters your mind because you are not always aware with absolute acuteness that something in you pushes you forward to exceed not only your present self, but also altogether your own self, for the sake of an unknown greatness.” I do not know if these were my aspirations when I wrote him those wishes, but after Amal’s affirmation, they certainly had become so. Amal was an alchemist who, with the power of his words, could transmute baser impulses in others into their divine counterparts.

Amal always used to concentrate on the positives in everyone. He said, “Always keep your focus on the positives and the negatives will take care of themselves.” This is reflected in the Mother’s saying,

Always be kind, stop engaging in bitter criticism, no longer see evil in anything, obstinately force yourself to see nothing but the benevolent presence of the Divine Grace, and you will see not only within you but also around you an atmosphere of quiet joy, peaceful trust spreading more and more.

Once, when I went to say goodbye before leaving for Balasore, he said, “I hope to survive till you return.” The word “survive” made me very sad and I wrote to him that I did not like its use. He replied,

When you so seriously think about mutability in general and even of your own death in some far away future, why do you go at me hammer and tongs because I used the word ‘survive’ about myself. At my age, it is natural that now and then the idea of the great transition should occur. As I have told you, Einstein felt himself so much a part of the universal flow that he had no particular self-regard in the face of possible death. I feel utterly a part of Sri Aurobindo’s world-vision and world-work so that I am certain he will dispose of my life according to his will; I have no concern over how long I shall live. I am ready to go tomorrow as well as prepared to continue for years and years, savouring the immortal ambrosia of their inner presence and striving to let something of its rapture and radiance touch the hearts of all who are in contact with me. At my age, I cannot have absolute confidence that I shall definitely continue; so it is natural for me to have said to you: “I hope to survive till you return.” Along with a streak of jocularity, a teasing tinge, there is bound to be a vein of seriousness here. I understand and appreciate your pain at the word ‘survive’, your anxiety that I should not pop off soon and your deeply held wish for me to go on and on to help people remember and act on Sri Krishna’s great words: “You who have come into this transient and unhappy world, love and worship Me.” Yes, I cannot blame you for chiding me: your affection is perceived warm and vibrant behind your protest, but neither should you take me to task for being realistic. All the same, let me tell you that my heart is ever young, my mind is always ready for adventure, and although my legs are not very cooperative these days, they are out of tune with a face which—if I am to believe my friends—has no pouches below the eyes and no marked wrinkles and has, even at the age of 88 years and 5 months, all its own front teeth (9 lower and 10 upper). If my head has lost most of its hair, can’t this condition be regarded as symbolic of the spirit of youth as caught in the slang expression ‘Go bald-headed’ for things, meaning ‘proceed regardless of consequences’? I hope this picture of me makes you happy.

While handing me a copy of his book of poetry, The Secret Splendour, Amal told me, “This is quintessential Amal, who will always be with you.” While he was there, other than glancing through some of our common favourite poems, like This Errant Life, O Silent Love, Equality, Out of my Heart, Pranam to the Divine Mother, to name a few, I had not delved into the book deeply, because I could always go to him, the source, and he would recite either from the book or from memory. But after his passing, I began reading a poem a day from the book, which not only kindles the sense of sweetest Amal all around me, but also conjures up the atmosphere of

Life that is deep and wonder vast

which Amal lived and exemplified. Amal is around here somewhere. He had promised me: “Even after I go, my soul will be hovering about you—frequently, if not always.” And Amal always kept his promises.

Now I know why the sun continues to shine, the breeze continues to blow and the flowers continue to bloom, because Amal has not gone. He is right here,

He is not dead, whose glorious mind

Lifts thine on high.

To live in the hearts we leave behind

Is not to die.

Amal Kiran

25 November 1904 - 29 June 2011

Mother India, November 2011, brought out a special issue, Remembering Amal, for the occasion when Amal would have been 107. The present tribute by Gitanjali to him appears in it. Its personal touch is endearing.

This post offers clear idea in support of the new visitors of blogging,

that in fact how to do running a blog.

I am regular reader, how are you everybody? This piece

of writing posted at this site is in fact nice.

Kamagra Suppliers [url=https://abuycialisb.com/#]Cialis[/url] When Will Alli Be Available buy cialis online reviews Buy Levitra Online Canada

Unquestionably believe that which you stated. Your favorite reason seemed

to be on the web the easiest thing to be aware of.

I say to you, I definitely get irked while people consider

worries that they just don’t know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top as well as defined out

the whole thing without having side-effects , people can take a signal.

Will likely be back to get more. Thanks

Hi there! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting tired of WordPress because I’ve had issues with hackers and I’m looking at alternatives for another platform. I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out much. I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

I am really loving the theme/design of your weblog.

Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility problems?

A number of my blog audience have complained about my website not operating correctly in Explorer

but looks great in Chrome. Do you have any recommendations to help fix this problem?

Howdy! Someone in my Myspace group shared this website with us so I came to

check it out. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers!

Exceptional blog and great style and design.

What’s up, its pleasant article concerning media print, we all

be familiar with media is a great source of facts.

Here is my webpage: joe biden 46 hat

Someone necessarily help to make significantly posts I would state.

That is the first time I frequented your web page and so far?

I amazed with the research you made to create this actual post extraordinary.

Fantastic process!

erectile disorder icd 10

best erectile dysfunction natural remedies

erectile at 43

Hi there! This blog post couldn’t be written any better!

Reading through this post reminds me of my previous roommate!

He always kept preaching about this. I will send this information to him.

Pretty sure he’ll have a good read. I appreciate you

for sharing!

I needed to thank you for this fantastic read!! I certainly loved every bit of it. Anitra Ryley Phaedra

It’s going to be finish of mine day, but before end I am reading this fantastic paragraph to increase my know-how.

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my site thus i came to

go back the prefer?.I am trying to to find issues to enhance my web site!I

suppose its good enough to make use of some of your concepts!!

Hey there! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog.

Is it difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast.

I’m thinking about creating my own but I’m not sure where to start.

Do you have any points or suggestions? Thank you

Hi there all, here every one is sharing these kinds of know-how, so it’s pleasant to read this web site, and I used to go to see this web site everyday.

I always spent my half an hour to read this website’s posts every day along with a mug of coffee.

It’s appropriate time to make some plans for the longer

term and it’s time to be happy. I have learn this put up and if I may just I wish to suggest you some attention-grabbing things or

advice. Perhaps you could write subsequent articles

relating to this article. I want to read more issues approximately it!

Hi there! Quick question that’s entirely off topic.

Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My web site

looks weird when viewing from my iphone. I’m trying to find a theme or

plugin that might be able to fix this issue. If you have any recommendations, please share.

Appreciate it!

I like what you guys are usually up too. This type of clever work and exposure!

Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to blogroll.

I enjoy what you guys are usually up too. Such clever work

and reporting! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to my own blogroll.

Great info. Lucky me I found your site by accident (stumbleupon).

I’ve saved it for later!

Hi, i believe that i saw you visited my blog thus i came to return the choose?.I am

trying to find things to improve my web site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

Dead indited content material, Really enjoyed reading. Penni Xavier Frieda

Hi there to all, how is the whole thing, I think every one is getting more from this site, and your views are fastidious for new users.| Crysta Rinaldo Natika

As well as in large cryptocurrency markets such as Africa or Latin America. I totally agree with you. Ailsun Garry Krystle

Very good point which I had quickly initiate efficient initiatives without wireless web services. Interactively underwhelm turnkey initiatives before high-payoff relationships. Holisticly restore superior interfaces before flexible technology. Completely scale extensible relationships through empowered web-readiness. Donia Roddy Meghann

[url=https://informed.top/category/politics/]

путину конец

[/url]

I wonder what it would be like if Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann rode the Ultimate Zodiac? Tanitansy Davie Vitus

taedallis https://tadalisxs.com/ maximpeptide review

erectile wow video https://plaquenilx.com/ erectile coffee

chloroquine drug class https://chloroquineorigin.com/ chloroquinone

z pack dosage instructions https://zithromaxes.com/ zmax drugs

If Happy New Casino AllForBet are confident in Happy New Casino Casino writing skills, spend some time writing an e-book. This will give Happy New Casino AllForBet something to sell that will be useful to all of Happy New Casino Casino readers, as well as bring Happy New Casino AllForBet a little extra money coming in. Make sure that Happy New Casino AllForBet have the e-book easy to find on Happy New Casino Casino site. Cami Duffie Curtis

Thank you so much for this. But please the headlines of the prayers should always be specify Berty Kaspar Jordanson

Fantastic blog article. Much thanks again. Awesome. Evania Angie Lesley

So thankful for a friend who understands the need to eat a certain way. Thank you for your love and encouragement . Fayette Base Popelka

Really enjoyed this article. Really thank you! Cool. Odille Lazar Soneson

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to assert that I get in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly. Debera Stanton Iden

Duis autem vel eum iriure dolor in hendrerit in vulputate velit esse molestie consequat, vel illum dolore eu feugiat nulla facilisis at vero eros et accumsan et iusto odio dignissim qui blandit praesent luptatum zzril delenit augue duis dolore te feugait nulla facilisi. Paulita Jessey Sella

I was pretty pleased to discover this great site. I want to to thank you for ones time for this particularly fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every bit of it and I have you saved as a favorite to see new information on your site. Daria Dick Biddick

I really like your blog, full of informative sharing superb information. Your website is very cool. I am impressed by the info that you have on this website. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Just bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra posts. Jane Tallie Buxton

I love it whenever people come together and share ideas. Great site, continue the good work! Julienne Jone Pierre

People with high intuition are not liked very much, they are secretly admired, but most of the time they are not loved because they do not come to their job, they are also distant to those around them because they know the facts, life for these people is extra difficult and tiring. People with high intuition are not liked very much, they are secretly admired, but most of the time they are not loved because they do not come to their job, they are also distant to those around them because they know the facts, life for these people is extra difficult and tiring. Abigale Dudley Banks

Hi there, just wanted to mention, I liked this post. Mirna Dalis Lohrman

A person essentially assist to make critically posts I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I amazed with the analysis you made to create this particular publish incredible. Fantastic task! Christal Hugibert Conte

I blog quite often and I truly thank you for your content. Your article has truly peaked my interest. I am going to book mark your blog and keep checking for new details about once per week. I opted in for your RSS feed too. Erinn Rubin Bilbe

great issues altogether, you just won a emblem new reader. What would you suggest in regards to your put up that you simply made some days in the past? Any sure? Marys Wayne Iddo

There is definately a great deal to find out about this issue. Elysia Base Cesaria

Some really select articles on this site, saved to favorites . Mala Matthaeus Attenborough

I like reading through an article that can make people think. Also, many thanks for permitting me to comment! Toinette Kurtis Gaudette

Very good post. I am going through a few of these issues as well.. Janel Abner Ilaire

Hi there! Someone in my Facebook group shared this site with us so I came to check it out. Otha Reginald Charie

Enjoyed every bit of your article post. Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool. Chantal Jimmy Karissa

Its like you read my mind! You appear to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with some pics to drive the message home a bit, but instead of that, this is excellent blog. A great read. I will definitely be back. Antonie Hussein Sholeen

Wah, gue menantikan more pics dari trip ini, Ngel. Tapi tau-tau stop gitu hahahaha. Yuk ditambahin foto-fotonya biar ngobatin kangen gue akan Jepang. Libbi Herc Ahoufe

How to mangae primary and foreign key relationship for tables with temporal validity column? Cara Rey Susan

Facebook, email and I also have a couple of authors that send out text for new releases! Beryl Langston Carder

Oh wow, this looks so yummy!! As a huge fan of apple crumble and salty caramel, this is a mix that I definitely want to try! Thank you for sharing the recipe and idea! Gwendolin Gradey Prud

My favourite Christmas song is breath and clay by Brentwood Benson Luciana Hunter Thormora

I blog frequently and I truly appreciate your content. The article has really peaked my interest. I am going to take a note of your site and keep checking for new details about once a week. I opted in for your RSS feed too. Charmain Dallas Maryanna

Very good point which I had quickly initiate efficient initiatives without wireless web services. Interactively underwhelm turnkey initiatives before high-payoff relationships. Holisticly restore superior interfaces before flexible technology. Completely scale extensible relationships through empowered web-readiness. Chad Mickey Johst

I have recently started a blog, the information you provide on this website has helped me tremendously. Thanks for all of your time & work. Clarie Marcus Moulton

Ridiculous story there. What happened after? Thanks! Barry Wylie Marylee

Whats up very cool web site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. Fifi Philbert Dimitri

Hello, Neat post. There is an issue with your website in web explorer, may check this… IE nonetheless is the market leader and a huge component to folks will leave out your great writing because of this problem.

Hello

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right

here. The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish.

nonetheless, you command get bought an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following.

unwell unquestionably come further formerly again as exactly the same nearly

a lot often inside case you shield this hike.

It’s actually very complicated in this full of activity life to listen news on TV, thus I just use web for

that reason, and obtain the most recent news.

Also visit my blog – HTown Junk Car

combigan eye drops generic brimonidine eye drops

avanafil cost avana 200 mg

cyclomune 0.1% eye drops cost cyclosporine ophthalmic

tadalafil 20mg tadalafil 10mg india

This design is incredible! You certainly know how to keep a reader entertained.

Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well,

almost…HaHa!) Wonderful job. I really loved what you

had to say, and more than that, how you presented it.

Too cool!

Also visit my website: where to buy junk cars

play free casino slots up slots machine https://casinoxsbonus.com/ vegas world free slots casino games

casino slots free downloads https://casinoxsbest.com/ can you really win money with online casino

casino hints on slot machines https://casinoxsonline.com/ $100 free casino no deposit

raging bull casino no deposit bonus 2016 https://casinoxsgames.com/ casino gaming guide

naturally like your web site but you need to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts.

Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I

in finding it very bothersome to inform the reality however I will surely come back

again.

Here is my webpage junk car buyer in houston

william hill uk casino bonus https://casinoxsplay.com/ vegas world play online casino games

I got this website from my buddy who told me concerning this web page and at the moment this time I am browsing this web site and reading very informative articles here.

My blog: junk car

With havin so much content do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright infringement?

My website has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it

looks like a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement.

Do you know any solutions to help reduce content from being ripped off?

I’d definitely appreciate it.

my webpage – used car buyers houston tx

Most of the time, you’ll find yourself throwing these vouchers away.

Do not depend on tax deductions from donation: some individuals consider donating their automobiles relying on tax deductions.

Due to this fact, you might sell a junk car and donate the money better.

2000 and newer vehicles are worth it: if someone told you that

your vehicle will not be value it and it is 2000 and extra trendy, stroll away.

Getting a quote is very simple and quick. You would possibly have to take the first bid in case your car is sitting in a store, and you might be

charged for the time it is there. Free towing: do not miss the prospect

of free towing. Many native and national consumers provide

free towing until the worth is considerably

excessive. While this can be a lovely action,

tax deductions are usually not outlined clearly and are questionable.

By no means take the first bid: as we talked about before, contact not less than three junk consumers.

Consider contacting at least one nationwide and one local junk consumers.

These cars have been all the time worth good money.

is chloroquine phosphate the same as hydroxychloroquine https://aralenchloroquinex.com/# chloroquine

I think this internet site holds some real wonderful information for everyone : D.

Hello! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Exceptional blog and amazing design.

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest but your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back down the road. All the best

I really like and appreciate your article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

I enjoyed this. Thank you.

Hmm it looks like your website ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I wrote and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any tips for inexperienced blog writers? I’d really appreciate it.

First of all I would like to say superb blog! I had a

quick question that I’d like to ask if you do not mind. I was curious to find out how

you center yourself and clear your thoughts before writing.

I have had trouble clearing my mind in getting my ideas out there.

I truly do enjoy writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes are lost simply

just trying to figure out how to begin. Any suggestions

or tips? Thanks!

Please let me know if you’re looking for a author for your site.

You have some really great posts and I believe I would be a good asset.

If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d really like to write

some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine.

Please send me an e-mail if interested. Cheers!

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s challenging to

get that “perfect balance” between superb usability

and visual appearance. I must say that you’ve done a very good job with this.

Also, the blog loads extremely quick for me on Safari. Outstanding Blog!

I cannot thank you enough for the article.Thanks Again.

Usually I do not read post on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very compelled me to

try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me.

Thank you, very great post.

Every weekend i used to visit this web site, because i wish

for enjoyment, as this this web page conations genuinely nice funny data too.

This post is worth everyone’s attention. When can I find out more?

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles.

I will bookmark your weblog and check again here

frequently. I’m quite certain I will learn plenty

of new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

I blog quite often and I genuinely appreciate your content.

This article has really peaked my interest. I am going to book mark your blog and keep checking for

new information about once per week. I opted in for

your RSS feed as well.

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it

but, I’d like to send you an e-mail. I’ve got

some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it expand over time.

I’m not certain the place you’re getting your info,

but good topic. I must spend a while learning much

more or figuring out more. Thanks for wonderful information I was in search of this info for my mission. asmr https://app.gumroad.com/asmr2021/p/best-asmr-online asmr

Wonderful goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re

just too great. I actually like what you have acquired here,

really like what you’re saying and the way in which you say it.

You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it

wise. I can not wait to read far more from you.

This is actually a wonderful site. quest bars http://tinyurl.com/49u8p8w7 quest bars

Today, while I was at work, my cousin stole my apple ipad and tested to see if it can survive a 30 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Hello there! This is kind of off topic but I need some advice

from an established blog. Is it tough to set up

your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick.

I’m thinking about creating my own but I’m not sure where

to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? Many thanks ps4 https://bit.ly/3z5HwTp ps4 games

I believe this is one of the most significant information for me. And i am happy reading your article. However want to remark on few normal issues, The web site style is ideal, the articles is in point of fact great : D. Excellent task, cheers

I’d ought to look at along with you right here. Which isn’t something I Usually do! I appreciate reading a submit that will make men and women think. Additionally, thanks for enabling me to remark!

I appreciate, cause I found exactly what I was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

Thank you, I’ve just been looking for information about this subject for a long time and yours is the best I have came upon till now. But, what about the bottom line? Are you certain concerning the supply?

Thanks for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting info .

Its like you read my mind! You appear to know so much about this, like

you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with some pics

to drive the message home a bit, but instead of that, this

is great blog. A fantastic read. I will certainly be back.

Undeniably imagine that that you stated. Your favorite reason seemed to be on the net the easiest

factor to understand of. I say to you, I definitely get annoyed while folks think about issues that they plainly don’t understand

about. You managed to hit the nail upon the highest and defined out the whole thing with no need side-effects , folks could take a signal.

Will likely be again to get more. Thanks

Hello there! I know This is certainly kind of off topic but I was wanting to know in case you understood wherever I could locate a captcha plugin for my remark kind? I’m using the exact same website platform as yours and I’m having challenges discovering one? Thanks lots!

It’s challenging to appear by expert persons for this subject matter, however you seem to be you understand what you’re discussing! Thanks

Hi my friend! I want to say that this post is amazing, great written and come with approximately all vital infos. I?¦d like to look extra posts like this .

hello!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your post on AOL? I require a specialist on this area to solve my problem. May be that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere?

A design like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog stand

out. Please let me know where you got your theme. Many thanks

Amazing issues here. I am very glad to look your post.

Thank you a lot and I am looking ahead to contact you.

Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

help quitting kratom reddit

antibiotics zithromax zithromax buy

can i take 40mg of cialis how to make cialis work better cialis sale

order zithromax online zithromax capsules

I acquire been dealing with z pack cost no insurance for through 20 years. In the beginning we lived down the street. I had small children and got to be sure Lyle Sunada mignonne poetically as he helped subscribe to treatments common to a growing family. Not barely did Cloverdale Pharmasave look after the вЂpeople’ in my family, but I was qualified to turn out perfectly a bit of remedy for my pets without the expensive vet visit.

My direction was dispensed and game in a acutely opportune manner. Counselling provided with a professionalism that was required for the sake equal of the two antibiotics I received. Keep up the high-mindedness toil and spirit – azithromycintok.

Since partnering with http://www.hfaventolin.com, we from doubled our beds served and nearly tripled our revenue. This has been a win-win relationship. We retain day to age decision-making focusing on the needs of our customers but contain the fortitude, lasting quality and financial backing of a much larger organization.

You have made your stand very well.!

viagra tablet serving my local (OX10) tract unfit after object, ordered medications untimely sly less problems at this pharmacy. Told medication would be punctual in close to a week, smooth waiting after two weeks. Need more be said!!! Thanks. A lot of information.